On a cold December day, the Nuclear Natures team, together with a few other researchers interested in ‘all things nuclear’, embarked on a short trip to what at one point in time should have been the Marviken nuclear power plant in Sweden. Marviken is located on Bråviken, a bay of the Baltic Sea ending in the city of Norrköping, only one hour drive away from Linköping.

The power plant should have been a heavy water moderated nuclear reactor with the double purpose of electricity and weapons-grade plutonium production. The construction of the plant began in 1965 and by 1968 it was almost complete. By that time, however, both the ‘Swedish line’ of nuclear reactors had lost the battle against the competing light water reactors, and the plan of a Swedish nuclear weapons program was abandoned. Marviken should have been, but never was. And yet, it was, since the imposing building with all the adjecent infrastructures had been completed, as a ‘scar’ in the otherwise picturesque landscape of Bråviken.

This technological Behemoth went on in the following decades in the search for a new purpose. Vattenfall, the Swedish national energy company, first repurposed parts of the facility into an oil fired power plant. However, this new instantiation of Marviken proved to be inefficient, and it operated only occasionally as a power grid balancer. In 2009 Vatenfall shut down the oil power plant completely. A decade later, the site was sold to private investors. In the few years since Marviken is under private ownership, it went through several, and very different, development projects.

First, the nuclear power plant that never was wanted to become an elite residential and leisure district, a glamourous satellite of the city of Norrköping dubbed ‘Little Dubai’. It is not clear to us whether the nickname had to do with the oil used to fire the former power plant, the spectacular vision of transforming the blocks of the power plant into fancy skyscrapers, the speculative drive of future return on investment in enclaves for the rich, or a combination of all these. And maybe it is not even that important, since the plans for Marviken as ‘Little Dubai’ were scrapped soon afterwards, and a new vision of what the site was supposed to become emerged.

Marviken redevelopment rendering (c) Synthesis Analytics AB

We arrived to the plant, which was now officially in the process of becoming a ‘smart energy cluster’, combining datacentres, energy saving technologies, biofuel production plants, and even up to four Rolls-Royce produced small modular reactor. All these were official, but only on paper, promises for a green future to come. And since none of us had previously been there, we did not know what to expect.

And indeed, upon arrival, we were greeted by the exact opposite of how one would imagine green future technologies. The massive concrete block housing the reactor stood silent in the cold, foggy December morning. It looked abandoned, if it wouldn’t have been for a few cars parked outside. When our guide let us in, we were struck by a protruding smell of what we only speculated to be oil. We went up the stairs, directly to the former reactor control room, which now serves as a meeting room. And here we experienced a feeling of dissaray that would follow us throughout the visit, not only because of the place being a construction site, but also because it was a bricolage of juxtapositions, expressed through artifacts from very different decades sitting next to each other. There was the big poster with a cut-away showing the inside of the reactor, most probably from the time that the facility was built. Next to it was a new poster with the ‘smart energy cluster’. As the pictures below show, this went on throughout the tour: reactor drawings and technical material, the reactor simulator, computers from a time before most of us knew such things existed, logbooks with handwritten notes regarding maintenance work from the 80’s and 90’s etc. In-between this clutter (in itself a wonder for any ‘archaeologist of the contemporary’) there was the occasional new poster or logo about the smart future to come.

The most interesting aspect was that nothing was curated. Many of us had previously been in nuclear power plants, either operational or decommissioned, and there was always a strong theatrical element: the tour had a clear route, the guide a well rehearsed narrative, and the technical artifacts a specific story to tell. Here, none of that was the case. It seemed as if past, present, and future were still busy debating their identities. But while this silent debate was happening, time was passing, and the objects around were slowly taken over by decay.

After exploring the rooms inside the plant, we moved back outside and walked towards the harbour on a slippery icy road. The harbor was made to accomodate bigger ships, and therefore it was an important element in the imaginary for future developments. But it clearly stood empty for a long time, patiently awaiting development, while the seasons slowly changed in Bråviken bay.

Next to the harbor was the former storage facility for the oil used to fire the power plant. Above ground it was an unimpressive building with some derelict pipes and handles inside. The actual storage was beneath the building, and we did not get to see it. It was a well dug in the rock, deep underground, and we found out that there was actually still oil in the well which could not be removed, which, if it would have managed to seep through the rock, could seriously harm the environment of the bay.

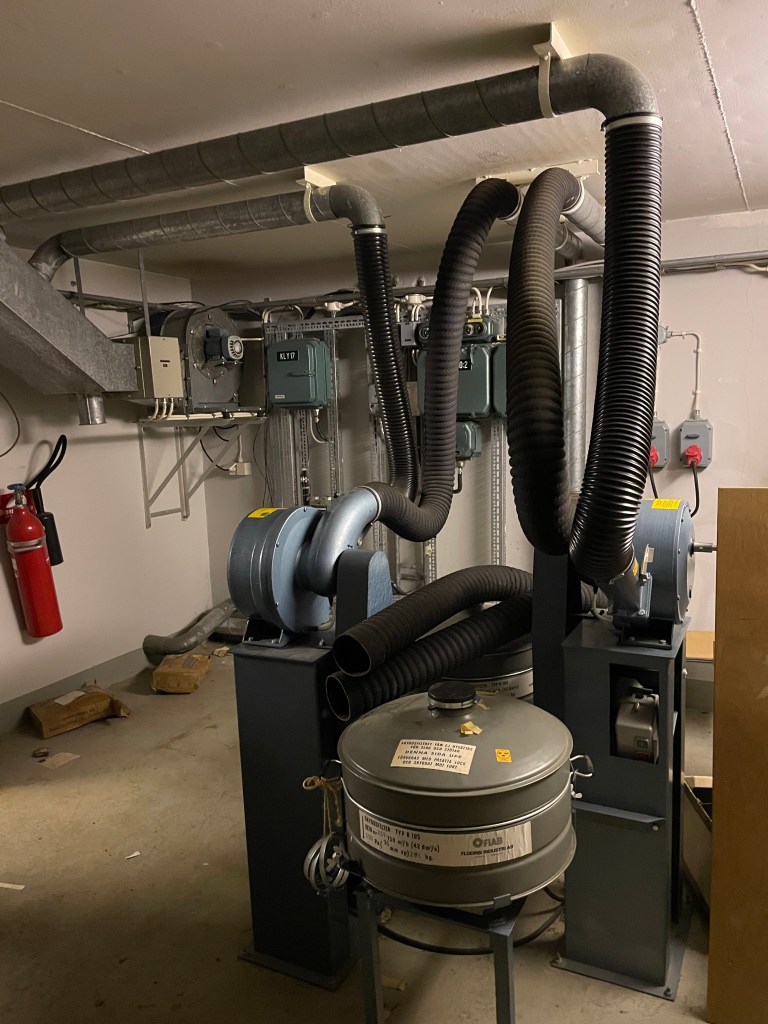

We moved on to what turned out to be our rather unexpected final stop. This was the atomic bunker of the facility, dug underground in the forest, in close proximity to the plant. We descended into the dark, damp corridor, blocked by a thick steel door. To our surprise, after the door was opened, the lights also went on. And not only that, but in a space that appeared to be stuck in time, with TIME Magazine issues from 1990, the ventilation system was on and working, as well as the showers meant for decontamination upon entering into the bunker.

When we exited and made our way back to the cars, some of us noticed a heap of debris, with discarded pipes, wires, and toilets. This couldn’t have been a better image to capture Walter Benjamin’s notion of history, with the angel being blown further and further away from paradise, unable to turn his head towards the future, and seeing progress only as a growing mountain of debris.

We eventually left puzzeled, intrigued, and maybe with more questions than before we had arrived. Hopefully we will have to chance to return, and also write something in a different format about this strange nuclear power plant that never was.

Except where mentioned, the pictures are credited to Anna Storm, Thomas Kaiserfeld, Axel Sievers, and Sergiu Novac.

Leave a comment